THE STORY OF LONGITUDE

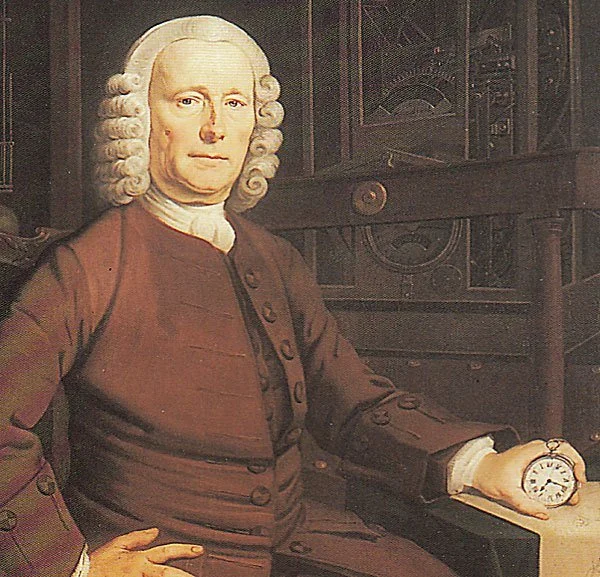

Driven by the death of his teenage son, John Harrison turns his obsession for building accurate clocks into a device that will save lives at sea.

He confronts the establishment, who believe that a self-educated carpenter from Hull, England, cannot possibly estimate time with the precision that is required to win the £20,000 offered by the Board of Longitude. They, and the mathematicians and astronomers who champion a more complex method mapping the moon and stars, put obstacles in his way: they change the rules, require spurious voyages to test his clocks, halve the prize money, finally take his inventions away, stall for time and insist he builds replicas.

The campaign against him costs 40 years of his life, his health, eyesight and risks his family falling apart. When he appeals to the King for justice, he is given compensation, but not the credit for his lasting contribution to sea faring. Fortunately, subsequent generations have come to appreciate his role and a special exhibition in the Royal Observatory at Greenwich celebrates his life and displays his four most important clocks.

WHY WAS THIS A PROBLEM?

A ship in the middle of the ocean needs to know its position if it is to avoid getting lost or attacked by pirates. How far north or south it is (latitude) can be easily estimated by looking up to see the highest point of the mid-day sun. If it’s straight above you, you’re at the equator. But knowing how far east or west you are (longitude) requires knowing how far you’ve travelled through the meridians or lines of longitude.

The Earth rotates one full turn (360º of longitude) in one day, which is one degree of longitude in 1/360th of a day, or every four minutes. To calculate your longitude, you therefore simply need to work out the time difference between noon at your location and noon at the Prime Meridian, set in Greenwich. In short, you need to know when you are, to know where you are.

For this, you need a reliable clock that works at sea, which is where John Harrison comes in.